The name Hayden's Light was a local moniker used by the folks living along the river. It honored a longtime lightkeeper named Gilbert Hayden who rowed to the lighthouse twice a day to light and then extinguish its sixth-order lens. Records I found don't indicate the fuel source, but it was probably kerosene.

Bernie Hayden also kept the Essex Reef Light. He may have been a relative of Gilbert Hayden, possibly his son. In Bermie Hayden's later years, his eyesight failed, but he continued to work as a lamplighter until the light was made automatic in 1919. A side note to his service: Mariners and local folk in Essex sometimes teased Bernie by saying the lighthouse has lifted off its foundation and floated away.

The keepers had several months' vacation in the winter when the light was extinguished due to ice on the river. They probably worked at jobs ashore from late December until March.

The Lighthouse Service decided to construct this lighthouse and one farther upriver on Chester Rock due to the high volume of ship traffic on the river. By 1880, sizable vessels traveled all the way from Long Island Sound up to Hartford. Congress appropriated $15,000 to light the river, which included the beacons at Essex Reef and Chester Rock.

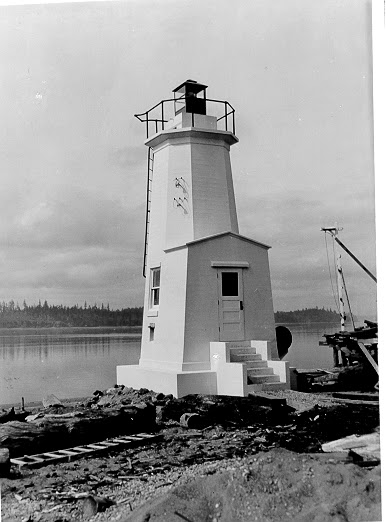

Both were built to the same specifications. The design called for a 25-foot wooden, shingled tower with a black lantern. A submarine foundation consisting of a wooden crib sheathed in metal and filled with rocks rose above the reef and the tower sat atop the crib on a concrete base. A ladder ran up the side of the foundation and the exterior of the tower for access to the lantern room. There was room in the base of the tower for storage of tools and fuel. Both the Essex Reef Light and the Chester Reef Light (shown below, photo from the Deep River Historical Society) displayed sixth-order Fresnel lenses. My research doesn't reveal the type of fuel used, but it probably was kerosene.

Essex Reef Light began its career in the summer of 1889 with a fixed red light. It was changed to fixed white in 1892. Chester Rock Light was replaced by an automatic skeleton tower in 1912, and thereafter no keeper was needed. Essex Reef Light continued in operation until about 1919 when it, too, was replaced by an automatic skeleton beacon. It was converted to a gas light in 1931. The whereabouts of the original sixth-order lenses for these lighthouses is unknown.

The Coast Guard replaced both lights with modern square steel towers by the 1970s. The image below, from Alex Trabas' website, shows the Essex Reef Light today. It's not as quaint and pretty as the old wooden tower, but it does the job.

The 26 foot steel tower is surmounted by a plastic beacon that flashes green every 4 seconds. A green dayboard has #25 on it, to identify the beacon in the lineup of river lights. Locals still refer to this as Hayden's Light. It sits off Hayden's Point, named for the first lightkeeper who rowed from his home on the point twice a day so long ago.