Raindrops pelted the

windshield of the helicopter on the morning of March 24, 2003 as I made my way to Cape Flattery

Lighthouse, a lonely sentry on Tatoosh

Island marking the

entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Our pilot, Ron, based in Olympia,

didn’t know much about lighthouses but assured us we would enjoy our visit to

this one. He had been there once to

deliver a researcher doing bird studies for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Today, he had three lighthouse nuts on his hands.

We had taken off from the small airport at Forks, a rainy, dark town known for its loggers, mushroom hunters, hearty diner food, and later, the setting of the "Twilight" series of books and movies. I had recently read a review copy of Our Lady of the Forest, by David Guterson. It was about a girl ho saw a vision of Mother Mary in the woods near Forks and how it changed her life drastically. This was a remote town with little traffic, and of that mostly passersby.

It was partly sunny on this day, however. Two friends were accompanying me---Bill Younger of Harbour Lights, who aimed to document the lighthouse for a future model of it, and Derith Bennett, a friend from Florida. If anyone was more nutty about lighthouses than me, it was (and still is) Derith. She aimed to touch every lighthouse in the nation if she could. Climbing them was even better. As a last resort, a view of them worked. It worked to say you'd been there.

The three of us had split the helicopter cost and gotten permission from the Makah Indians to land on Tatoosh Island. We would touch this lighthouse! U.S. Fish & Wildlife claimed we needed their permission to go, but the Makah scoffed, reminding us that they owned the island and could take visitors to it at their leisure. That meant they were sending along three of their tribal board members...at our expense. We were okay with that and willing to treat them to a helicopter ride as a way of thanking them for smoothing the waters to the island (though we wouldn't be going by boat!). I had books for them, and Bill had a few Harbour Lights figures to give them. Derith had a bag of candy to share. Gifts remain important, even today, when you visit tribal members after they have offered courtesies and kindness.

|

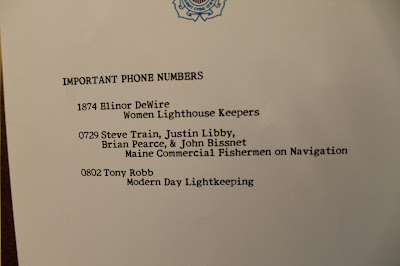

| The collapsed building is the old weather station. |

The

chopper lifted off its pad at Forks and bounced a bit as it rose. Each of us wore a headset, and the conversation was excited. I wasn't sure if the best part was the helicopter ride in one of those choppers with a big clear viewing bulb on the front, or the chance to visit Cape Flattery Lighthouse without getting wet. I had heard numerous nightmarish stories about people trying to land at the island in canoes, kayaks, zodiacs, motorboats, and more. It wasn't an easy place to access.

Clearing the trees and the town, the chopper turned almost due north. A panorama of Douglas firs and red cedars came into view and grew smaller as we gained altitude. The helicopter jostled lightly in the thermals above Olympic National Forest, then bounced

energetically as we flew off the coast.

The staggering beauty of rocks, stacks, arches, and caves left me breathless. The sea was an unbelieveable blue, almost navy blue. It had to be rich with nutrients for all the fish, seals, whales and other animals living in or near it. Far offshore, large tankers were on the horizon. This was what lighthouses were for, I reminded myself, though not as much today as when this lighthouse was built.

Ron turned back inland toward Lake Ozette, and a huge herd of elk came into view. He has spotted them and was giving us a little extra tourist experience. Each elk looked like it carried its own beige pillow on its butt! The herd began running in all directions, unhappy with the noise we made as we passed over them. These wild, wild creatures surely thought we were some sort of enormous bird passing overhead.

The lake was a blue-green jewel with clouds reflected on its surface.

"I really wanted you to see this area," Ron said. "This is wilderness country. It looks a lot as it did centuries ago. There's an old Makah village that's been dug up on the north side of the lake. I can just imagine it, maybe 300 or 400 years ago. The people working around their lodges, children playing and dogs barking, and curls of smoke rising from cooking fires. I've heard a massive mudslide came down that hill behind it and destroyed the whole village at some point in the past."

Moments later, he turned us almost due west and took us back over the Pacific. Raindrops suddenly began spattering the clear windshield and bulb of the chopper...then ice pellets, and finally snowflakes. They left rapid, streaking trails on the glass...or was it plexiglass. A March day here can deliver almost any kind of weather.

Below us, the counterpane of shoreline left me awestruck. An apron of aqua-blue was stretched between the headlands at the lake, with a white lacy fringe where it met the brown shore. I could see wave after wave pounding the rocks and stacks, slowly chiseling them into fantastic shapes. We rounded the headland behind the archaeological dig at the old Makah village, and Tatoosh Island

came into view, eighteen surreal acres draped in sunbreaks and leaden

clouds of a blustery spring day in the Pacific Northwest.

From this vantage point, it was easy to see and feel the isolation of the place. The line of horizon separating it from the mainland seemed miles long, but I knew it was barely a mile. And a treacherous mile for sure, a stretch of unforgiving deep blue water where rocks reposed. It had claimed ships and lives for centuries. Even the lighthouse keepers' dreaded it. One of them named Rasmussen drowned returning from shore in the 1934. A keeper's son also drowned, this time trying to help with a rescue of two navy personnel.

Only Old Doctor, a wizened and hoary Makah had no fear of this patch of Pacific and would push his log canoe into the water at Neah Bay and paddle to Tatoosh Island to deliver the keepers' mail and groceries.

As

we drew nearer the island, I noticed that many of the station’s buildings were in disarray

or missing entirely. At one time, around 1935, this

was a busy island with about forty residents – lightkeepers, navy personnel,

weather service forecasters, and lots of children, so many that a schoolhouse had to

be built. Today, it looked desolate, abandoned, uninhabited except by seabirds. I saw a small curious building that looked new, though, east of the lighthouse compound. I made a mental note to find it once I got on the ground. Despite the sense of loss and deterioration, Tatoosh Island was beautiful from the air, a giant table sitting in the sea and draped with a bright green cloth!

The

helicopter descended and touched down lightly on the large X in the middle of

the old Coast Guard helopad. My two friends and I jumped out and cleared

the blades, allowing the pilot to take off again for Neah Bay

where he would pick up three members of the Makah tribe and bring them to the island. I was looking forward to their stories and information.

We three broke up our small clique temporarily and began scoping out the buildings. We'd barely begun surveying when a brief and

intense rain shower forced us to take shelter under the eaves of the foghouse. It was gone minutes

later, and sunshine bathed the island. Everything

glistened with magical wet sheen.

My sneakers were now wet, but it was of no consequence. I tied the laces tightly and slipped off the hood of my raincoat, ready to go exploring again. No sooner had I done this than hail arrived, singing a clattering song as it bounced off hard surfaces. How many such storms had the light station seen in its career, I wondered. Hail collected on my notebook, and a few pellets even went down the collar of coat and slid down my back.

The sound of helicopter blades was heard in the distance. Ron was returning with our Makah friends. They landed and hopped out with big smiles, not for us particularly but for the island which had long been a part of their history and culture.

Makah

ancestors named the island for a legendary chief, Tatooche, a great seal hunter. They processed fish, seals, and whales on its

northeast beach and grew potatoes on the flat top. When the government decided to build a lighthouse

on Tatoosh Island in 1855, the Makah signed a peace

treaty and provided assistance to the work crew. The tower cost $39,000 and was lit December 28, 1856, Washington's third lighthouse. The Indians continued to help out by bringing

supplies and mail in their canoes, but the first three lightkeepers felt uneasy

and soon resigned.

It

was a matter of cultural ignorance, said Jeanine Bowchop, head of the

Makah tribal council and one of the three tribal members who had joined us. “The early keepers

simply didn’t understand the Makah way of life,” she told me as we walked the grounds together. Later, lightkeepers

would not only accept the Makah but happily join in their potlatches and

dances. Much of the tribe’s history

since 1857 commingled with that of the lighthouse and its keepers.

The

brick and stone tower wore a worn and weary countenance on this day, belying

its distinction as the lower forty-eight’s most northwesterly sentinel. I inspected it closely and found it sound,

but much in need of repairs and another face-lift. It was fixed up in 1999, but the force of the weather on Tatoosh could scour paint and whitewash in a hurry. The foghouse was disheveled. The derrick was a shambles, and the old

concrete radio compass and decoding station had collapsed into a pile of

rubble. On the island’s southeast side

I found the most tender remains, two graves surrounded by daffodils and a white picket

fence.

A Vega-type beacon shone in the lantern. It would be decommissioned a few years alter and the light put on a fiberglass pole to the west of the lighthouse. In its earliest years, the lighthouse had an opulent first-order lens, then a fourth-order lens. A steam fog whistle was added to the station in 1872. It later became a siren and then a horn. Today, it is silent. Mariners rarely use fog signals these days.

The

Coast Guard had maintained the beacon in good working order, as well as the small cemetery, but the grounds and

buildings had been given little attention since automation in 1977. This is often the

case at offshore lighthouses. Away from

public view, they fall into decay easily and become the targets of vandals. I doubted any vandal in his or her right mind would try to get out to Tatoosh Island.

The

Makah expressed interest in acquiring the lighthouse when it was relinguished by the Coast Guard. “It’s an important

part of our heritage,” Jeanine Bowchop told me before we departed Tatoosh. “We want to preserve it as much as any other

part of our tribal history.” She added

that this site is not easily accessed, and the lighthouse may never serve as a

museum or inn. But it should be saved. “We don’t want the birds here to become

extinct and that goes for the lighthouse too.”

In 2009 the Coast Guard did a complete clean-up of the island and removed any dangers--old oil tanks, defunct gasoline generators, other equipment. The lighthouse and its remaining buildings were turned over to the Makah.

Oh, did I forget to tell you what that small, new building was I saw from the air? It was a composting outhouse added by U.S. Fish & Wildlife. I know because I used it!

Photos are from the author's collection, Jim Gibbs, Coast Guard Museum NW.