In honor of Women's History Month, enjoy these articles.

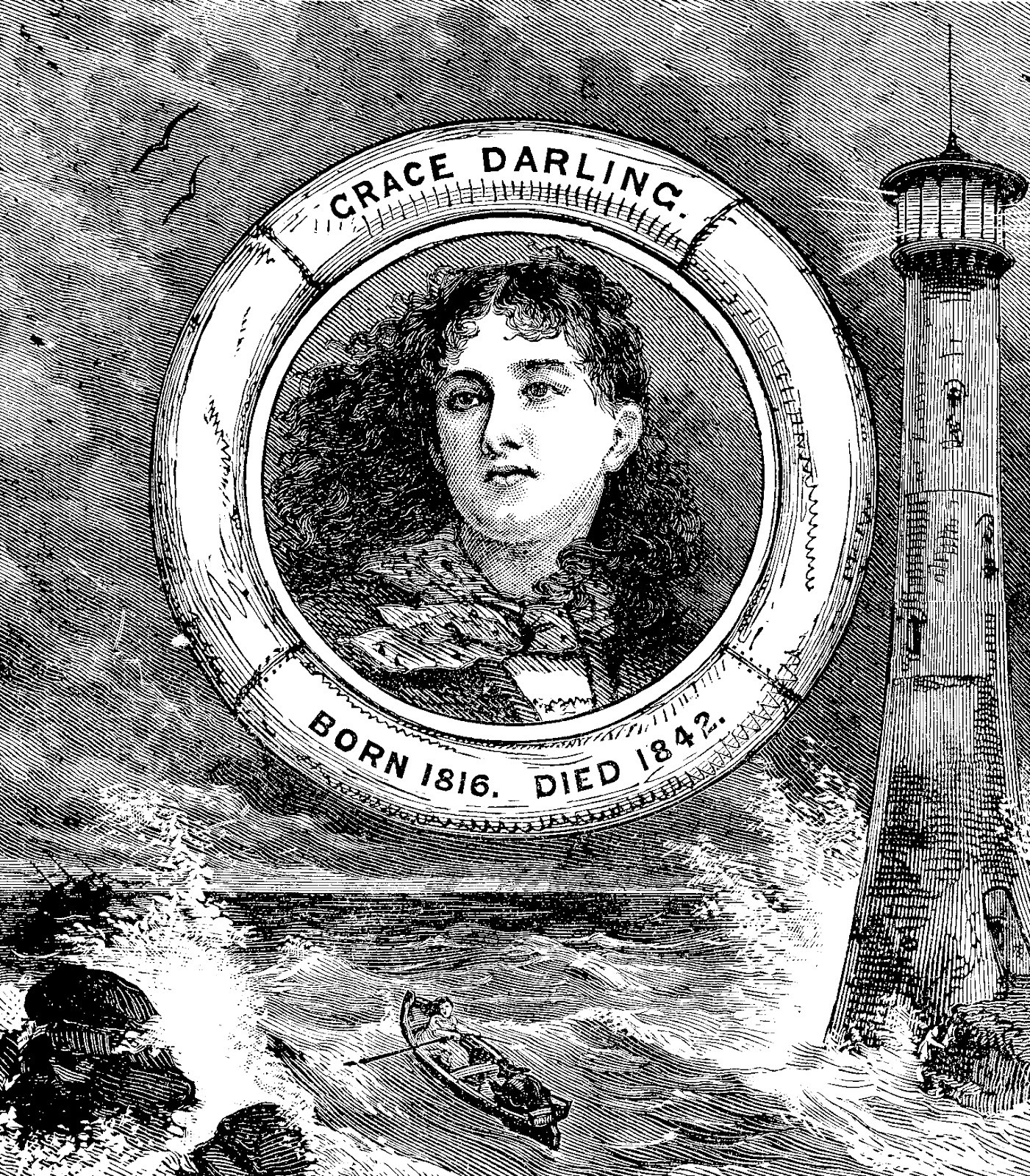

Grace Darling

Extraordinary Rescuer or Media Heroine?

Elinor DeWire

‘Twas on the Longstone

light-house,

There dwelt an English maid;

Pure as the air around her,

Of danger ne’er afraid…

Cal Bagby,

“The Ballad of Grace Darling”

What lighthouse

enthusiast has not heard of Grace Darling, the daughter of an English

lighthouse keeper whose pluck and call to duty in 1838 resulted in the rescue

of the survivors of the wrecked steamship Forfarshire? Thanks to flowery

Victorian journalism and the British bent for fanfare, Grace’s single gallant

deed earned her immortality and made her, as biographer Jessica Mitford said,

“the first media heroine.” Yet, her story is barely a glimmer these days…not

the popular and embellished tale it was more than a century ago. Who was Grace

Darling really, and was she as heroic as history claims.

I first heard about

Grace Darling from my mother, a great reader and amateur historian who, though

she never visited

Grace’s story grew

from simple roots into florid blooms. At dawn on September 7, 1838, Grace and

her father, William Darling, the keeper of the 1826 Longstone Lighthouse in the

Keeper Darling, in the

tradition of all lighthouse keepers, waited for low tide and greater daylight,

then donned his oilskins and downed a hot drink to steel himself for the

grueling task ahead—attempting a rescue of the survivors. The surfmen at

His twenty-two-year-old

daughter, Grace, knowing her father needed help, asked to accompany him. She

was young and could handle a boat. The only other person at the lighthouse was

her mother, and the elder woman had less strength than Grace. Who knows what conversation

passed between Grace and her father? It was a miserable chore to push a small

boat into stormy seas. They knew they’d be risking their lives to save others.

But this was the way of God-fearing coastal people, especially on the

Blankets were gathered, and the lighthouse coble, a short, flat-bottomed boat 21½-feet long from stem to stern, was lowered into the wild waters. Grace and her father were able rowers, but the mountainous seas and violent tide pushed the stout little coble off course several times, making the journey to the stranded ship twice as long. They reached the wreck—the steamer Forfarshire—in about an hour and Keeper Darling took off five of the nine survivors while Grace steadied the coble. The boat could hold no more than seven safely, so once loaded they rowed for the lighthouse. The lightkeeper and two of the rescued seamen then made a second trip to the wreck to fetch the remaining survivors. Grace did not accompany them this second time. Instead, she remained at the lighthouse with her mother to help the castaways, one of whom was badly injured.

What makes Grace

Darling a heroine for this effort? It was, after all, only one trip to the

wrecked ship, with Grace merely rowing and steadying the boat. Her father did

the actual rescuing and made two trips to the wreck. It was strenuous, to be

sure, but the Darlings were skilled boat-handlers and observers of the sea.

According to a naturalist in Seahouses, “I shouldn’t think their lives were in

much danger.” Indeed, “The Deed,” as local Northumbrians call Grace’s act, might

not have been worthy of the fame that followed.

Several lighthouse

women later equaled or surpassed Grace Darling’s effort. The

Rescuing and other

acts of self-sacrifice were commonplace among light keeping families. Longstone

lightkeeper William Darling, had done it before and would do it again. It was

expected of his compassionate, solicitous occupation. To have his daughter help

him row to the wreck was nothing extraordinary. Lighthouse history is replete

with daughters who helped their fathers in myriad ways.

Shipwreck was

commonplace too, especially in the tumultuous

Grace’s rapid rise to

fame was rooted in the Forfarshire

rescue, but other factors may have contributed more, including the tenor of the

time, a rising literacy rate, and the public’s fascination with women who

challenged the feminine archetype. Names like Joan of Arc, Lady Godiva, and

even Queen Victoria, who had recently ascended the British throne and proven

herself a capable monarch, resonated with a nation that seemed on top of the

world. Everyday people, especially girls and women, could read and write by the

early nineteenth century. Grace Darling herself was educated, an avid reader,

letter-writer, and keeper of journals. Books, newspapers, and magazines rolled

off the presses in her day, readily accessible. The time was ripe for a good

heroic story.

Three days after the

wreck of the Forfarshire the weather

broke in the

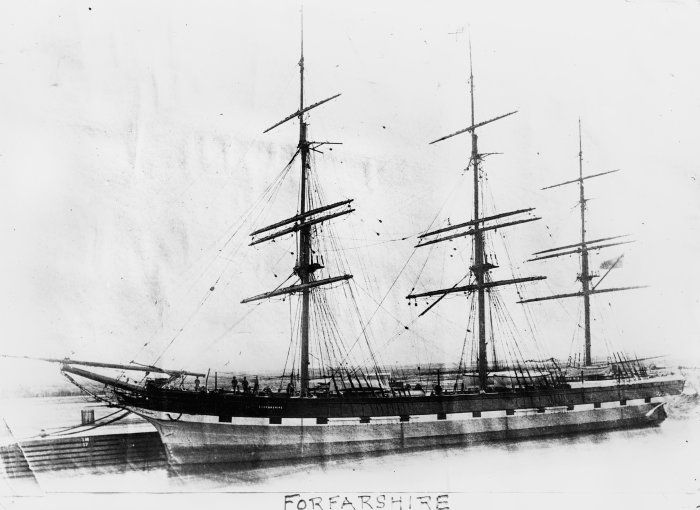

The ship was a

paddlewheel steamer with brigantine rigging. She was British-built and only

four years old—a cross-ship capable of

making her own steam power or using sails. This was the age when steam engines

were available but not always reliable, so ships carried both types of motive

power. Forfarshire had departed from

Some of the passengers

and crew managed to launch a lifeboat and were later picked up by a passing

schooner. The rest of them spent a horrific night as cold, heavy seas pounded

the ship and tore away her stern quarterdeck and cabins. Ultimately, she broke

in half. Some perished in the frigid waves or drowned on deck from the heavy

wave-wash. Others were killed outright when they were slammed into wooden and

metal parts of the ship. At dawn a few passengers still clung to the rails,

including a keening Mrs. Dawson who held in her arms the limp, dead bodies of

her two children, ages seven and nine. In the end, more than forty perished and

only nine survived—the nine rescued by the Darlings.

The first inquest into

the sinking reported that the ship foundered due to “the imperfections of the

boilers and the culpable negligence of Captain Humble.” This was based on the

decision that Humble should have sailed for the nearest port the moment the

boilers failed. Instead, he pressed on under sail, let his ship founder, and

was responsible for the loss of lives and cargo, not to mention an almost-new

ship. Humble had gone down with his ship and was an easy scapegoat. A second

inquest was kinder to him, laying most of the blame on the weather.

When the scandal died

down a few days later, a “penny-a-liner” reporter grabbed the Grace Darling

story for his gossip broadside and gave it his melodramatic best. He aimed to

milk the tale for all it was worth. Single-page broadsides were cheap entertainment

for the masses at this time, and broadside writers seldom cared about

journalistic ethics. If it sounded fantastic, it made news, often embroidered

with questionable details until it bore little resemblance to the truth. Our

current-day, scandalous tabloids no doubt grew out of these broadsides.

The Grace Darling tale

was one of the first to explode into an international story, complete with purple

prose, hyperbola, and feminine idolatry. The histrionic tale caught fire and

leaped from newspaper to newspaper, reaching The Times in

One newspaper reporter

identified as M.A. Richardson, said:

“Surely imagination in

its loftiest creations never invested the female character with such a degree

of fortitude as has been evinced by Miss Grace Horsely Darling on this

occasion. Is there in the whole field of history, or of fiction even, once

instance of female heroism to compare for one moment with this?”

Painters rushed to

Longstone Light to capture Grace’s delicate features, then painted her into

exaggerated scenes of angry seas and suffering humanity. Those who couldn’t

meet her in person took license and drew her as they imagined, a slender,

pretty young woman at the oars of a boat or about town wearing a fetching

bonnet. The versions of her face are so many and varied, we have little idea

what she really looked like.

Poets and minstrels

wrote tributes to the “Grace of womanhood and Darling of mankind.” Peddlers

hawked phony locks of her hair and swatches of fabric supposedly from the dress

she had worn on the day of the rescue. Anything Grace had worn, touched, or

owned fetched a high price. Marriage proposals came by the dozens, none of them

of interest to Grace. She wanted only the solitude of the lighthouse, her

family, and her books—not untypical for a lighthouse daughter.

A public subscription

for the Darling family raised a gift of several hundred pounds, to which the

Royal Humane Society and the National Institution for the Preservation of Life

from Shipwreck—the predecessor of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution—added

gold and silver lifesaving medals and a silver tea set. Even Queen

She spent her next few

years contending with the media, such as it was in the 1830s. There was no

Internet, Twitter, or Facebook, or even a You Tube, but Grace went viral in the

only way possible for her day. She “graced” the covers of newspapers,

magazines, and books, even special sheet music written in her honor. She

appeared on sailing cards, church fliers, and advertisements. Girls copied

Grace’s quiet, gentle demeanor and simple dress. Young men wrote poems alluding

to her valor and maternal potential. And

she was besieged with mail, visitors to the lighthouse, requests for her

signature and personal effects, of which she probably had few. She was the

adored model of young womanhood, a perfect suffragette—feminine and obedient, brave and steady of mind and heart, yet

capable of rowing a boat like a man to rescue “those in peril on the sea.”

In his 1841 book, The

Tragedy of the Seas, Charles Ellms wrote of Grace’s mettle during the Forfarshire

rescue:

“This perilous

achievement stands unexampled in the feats of feminine fortitude. From her

isolated abode, when there was no solicitation or prospect of reward to

stimulate, impelled alone by the pure promptings of humanity, she made her way

through desolation and impending destruction, appalling to the stoutest heart,

to save her fellow-beings.”

The 1839, Maid of the Isles by Jerrold Vernon

established Grace as “the girl with the windswept hair” and prompted even more

paintings that showed her tresses streaming and lustrous behind her as she faced

impossible seas. Those flowing locks are ironic, almost comical, since it’s

almost certain Grace’s hair was tied up in rag strips to make it curly—the

custom of the day. At so early an hour with a shipwreck sighted, would she have

taken time to do her hair? It’s doubtful. She likely went rescuing in her

curlers.

Unfortunately, much written

about Grace in popular literature is fabricated. Her older sister, Thomasin,

tried to set the record straight in 1880 with a small booklet in which she

wrote that “accuracy has suffered” and “romanticists” had colored “The Deed”

with untruths. Thomasin was particularly disturbed by the often-printed

assertion that Grace had beseeched, even begged, her father to go to the wreck

and that he had been reluctant. This probably was untrue, but it made good

dialogue and translated well for the stage productions that followed. Drama

aside, William Darling had gone out to shipwrecks before and would have gone to

this one without prodding. More often than not, lighthouse keepers put their

own lives in peril to save others.

We do know Grace was

deft at handling a boat, as were most light keepers’ daughters. From an early

age, she was rowed ashore to the family garden plot or to pick up supplies in

Bamburgh. Later, after about age twelve, she rowed to Bamburgh alone. Thomasin

lived in the village, and Grace paid her frequent visits. Like any teenager,

Grace enjoyed her sister’s company and partook of some of the fun ashore. The

oars to the coble were analogous to the keys to car today. We must not forget,

though, that she grew up in a community that relied on the sea for its

livelihood and for transportation. Yet….Northumbrians bore as much disdain for “the

deeps” as adoration.

“The sea is a lover,

but the shore is a deceitful whore,” was a popular metaphor repeated by sailors

in coastal taverns everywhere, most of whom had a love-hate relationship with

the sea. Hardly a family in Northumberland was untouched by “sea change.” The

local cemetery was rife with epitaphs alluding to saltwater occupations, drowning,

and shipwreck. Grace held the same view of the sea as her neighbors, an outlook

colored by religious faith, a healthy fear, and duty. Whatever happened on or

near the sea was God’s will and a test of human strength and endurance. Sacrifice

was expected, and not to be lavishly rewarded. Grace’s letters after the Forfarshire wreck reveal that she hated

all the attention focused on her.

Ironically, the citizens

of Northumberland disliked it too. They saw nothing unusual in Grace Darling.

Numerous writers of the day noted the community’s contempt for the media circus

surrounding the event and the absurd idolatry of Grace. It was much the same

disgust we experience today, with outrageous personalities like Lindsey Lohan,

Tom Cruise, and the Kardasians. Travel writer William Howitt, who had met Grace

Darling in 1840, discovered that people ashore were blasé about the Forfarshire rescue. One girl said, “It

was low water and the sea was smooth; anybody could have done what she did.”

Others flat-out denied that the rescue even happened, claiming it was contrived

and intended merely to sell papers.

While Grace attempted

to elude the media and cope with her sudden fame, her health declined. Visiting

her sister, Thomasin, in April 1842 she experienced chilblains and developed a

cough. Back at Longstone she grew worse, so her parents sent her back to Bamburgh

to live with her sister and be closer to a doctor. There was little that could

be done for lung infections in those days. By September Grace was bedridden and

the end was near. “She went like snow,” Thomasin told their parents. Grace died

on October 20, 1842. The diagnosis was consumption, today known as

tuberculosis.

It was a tragic finale

to a brief career. Grace was buried in the St. Aidans churchyard at Bamburgh in

a simple grave; yet, hundreds came to pay their respects. A distraught public

gave money for a monument to honor her, and an admiring sailor requested that Grace’s

memorial be large enough and placed in such a location as to be seen easily

from sea. The cenotaph, a canopied stone memorial minus her body, was built not

far from her grave. above)Its stone effigy of Grace, hands folded as if asleep after

her arduous labor of rescuing, or perhaps after the more difficult task of

coping with instant fame, put her to rest. The memorial lasted forty years

before it crumbled and a new one of similar but stronger design was built. The

plaque on the memorial reads: “Pious and pure, modest, and yet so brave, though

young so wise, though meek so resolute,” a dedication from poet William

Wordsworth.

Even in death, Grace

Darling’s legend continued to grow. It enlarged by turns until it shone

brighter than any lighthouse in

The remains of the Forfarshire

have a less glorious history. Parts of the ship still lie at a depth of

about 12-fathoms off Big Harcar Rock in Piper Gut. Nearby Hull Marina has

erected a plaque to the ship, and in a pub in Seahouses is one of the salvaged

nameplates. The town of

Grace, on the other

hand, has her own museum that was opened in Bamburgh in 1938 by the Royal

National Lifeboat Institution on the centennial of the rescue that made her

famous. Fortuitously, it is located near the house where she died and across

from the churchyard where she is buried. Visitors can learn her story and view

some of her personal effects and the famous coble she rowed to the wreck, as

well as see portraits and mementos from the Forfarshire

and a variety of souvenirs created in the wake of her popularity—mugs, candies,

hand-scribbled poems, postcards, music boxes, clothing, and more. As with most

media heroines, Grace has been commercialized.

School children visit

the museum (above), still marveling at her courage and singing “The Grace Darling”

song. They view the many artifacts attesting to her mettle, buy a knick-knack

or two, and leave chattering about storms and ships and brave young girls. Legend

or not, tabloid icon or moneymaking image, Grace Darling surely did something amazing

that stormy day in September 1838, an act beyond the expectations of any ordinary

woman of her day. This kernel of truth is what truly matters.

(Reprinted from the U.S. Lighthouse Society Keepers Log)

From the newsletter of the Point Fermin Lighthouse Society--