Olympia was settled in the 1840s and became the capital of Washington Territory in 1853. When Washington became a state in 1889, Olympia naturally became its capital. The name Olympia honors the beautiful Olympic Mountains to the west of the city.

As Puget Sound became settled, more and more vessels began traveling north and south. The Mosquito Fleet, a nickname for the many passenger steamers that plied the sound, grew in the middle 1800s. Vessels called at Olympia and ferried passengers to places like Tacoma, Seattle, Bremerton, and Port Townsend. In addition, Olympia grew strong as lumber and fishing port. To handle the many ships and ferries, Percival Dock was built in 1887.

With so much maritime activity, merchants and seaman began calling for navigational aids. There was little money available from Washington, D.C. and the Lighthouse Board. With a slim budget, buoys were placed and lights were established, most of the lights in the style of those that operated on small waterways and rivers--post lights.

On December 13, 1887, a 12-foot high wharf post with a lens-lantern light was set up on the northeast side of Budd Inlet, an important turning point for ships headed in and out of the port of Olympia. The site was Dofflemyer Point, a shoal-ridden area named for pioneer Isaac Dofflemyer who settled on the point in 1865.

In 1887, post beacons were also set up at other critical spots on Puget Sound, including Browns Point in Tacoma, Point Robinson on Vashon-Maury Island, and Alki Point in Seattle. (The lens-lantern pictured above is from Alki Point.) Most of the keepers were lamplighters who lived nearby and came to the sites to tend the beacons. The kerosene reservoirs on the lens-lanterns held enough fuel for eight days, so they were only refueled once a week. A local resident was hired to maintain the beacon at Dofflemyer Point, along with two other minor lights in the area.

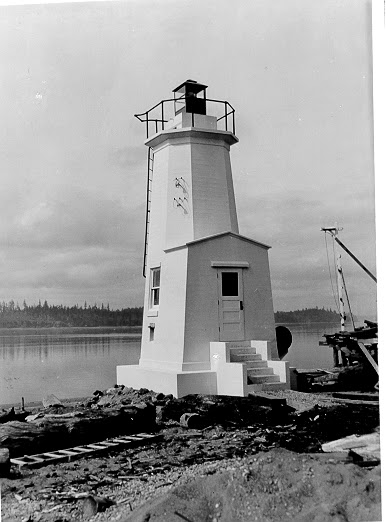

As Olympia grew, complaints about the maze of waterways leading to it mounted. The port was not a high priority for the Lighthouse Service funding sources in faraway Washington, D.C., but finally, in 1934, the post light was upgraded and placed on a 34-foot octagonal concrete tower with a tiny iron lantern on top. Inside the lantern was a small drum lens illuminated with an electric bulb. An electric air horn was added as a fog signal. (There was probably a fogbell prior to this.)

|

| B&W photos courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard |

The light operated self-sufficiently using a sensor, but the foghorn operated manually. For many years after World War II, the fog signal was tended by a local

woman named Madeleine Campbell, whose beach home was beside the lighthouse. Campbell switched the foghorn on and off as needed. Thus, she had to keep watch on conditions at Budd Inlet daily.

The

light was automated in the 1960s with a plastic optic. The small lantern was

removed. The horn was manually operated by Campbell for another twenty years before it,

too, was made self-sufficient. In 1987 a radiobeacon was added to the

lighthouse to further assist mariners.

In 2006 the Coast

Guard removed the historic fog signal, much to the dismay of the Little Boston

neighborhood. It was no longer needed and there was no response to the “Notice

to Mariners” the Coast Guard published. A small grassroots group in the town

hopes to have the foghorn reinstated.

The light remains active and is visible

for 9-miles. It sits on a private beach but can be seen from a nearby marina.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I welcome your comments, photos, stories, etc.!